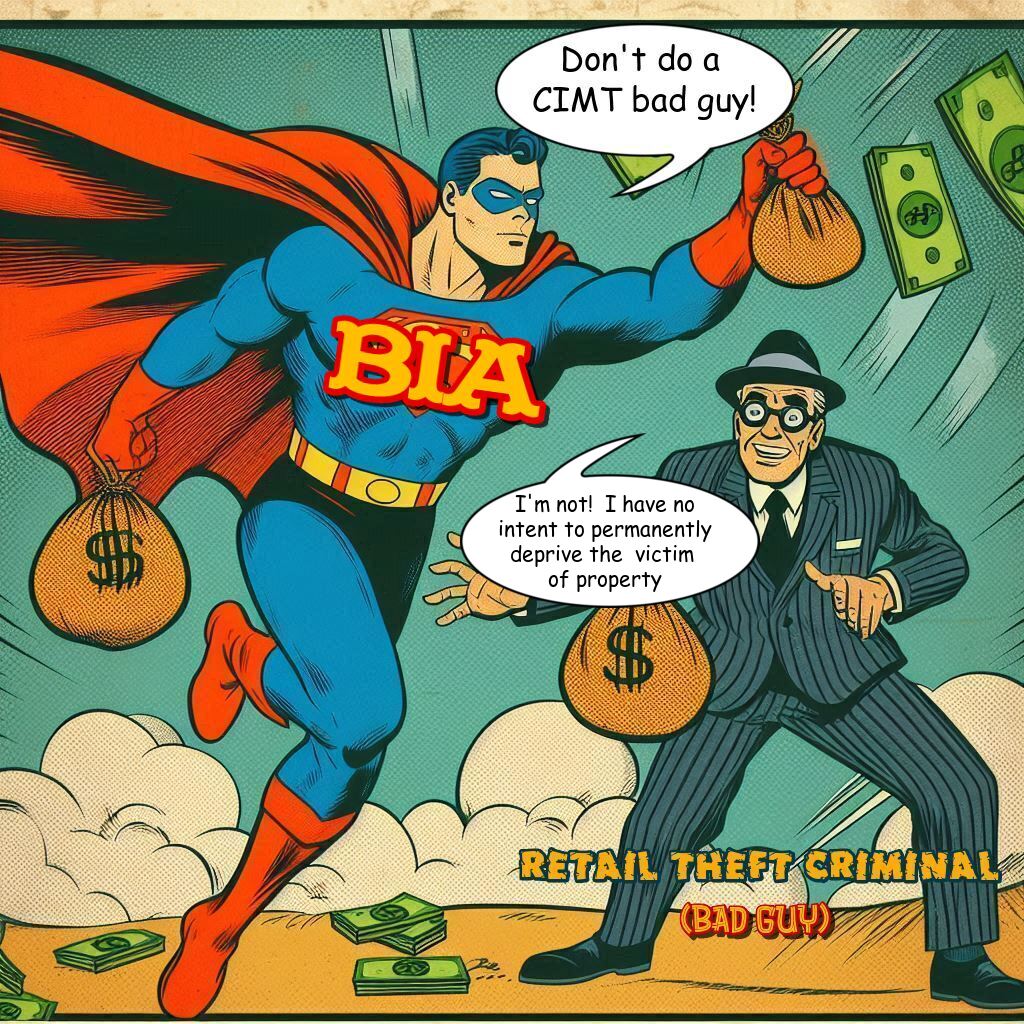

BIA’s Decision in Matter of Thakker

September 20, 2024, the Board of Immigration Appeals issued a decision in Matter of THAKKER, 28 I&N Dec. 843 (BIA 2024). Matter of Jurado, 24 I&N Dec. 29 (BIA 2006), aff’d sub. nom. Jurado-Delgado v. Att’y Gen. of U.S., 498 F. App’x 107 (3d Cir. 2009), overruled in part. In Matter of Thakker, the Board … Read more