Immigration Judge WebEx Links For Immigration Court (UPDATED 4/2024)

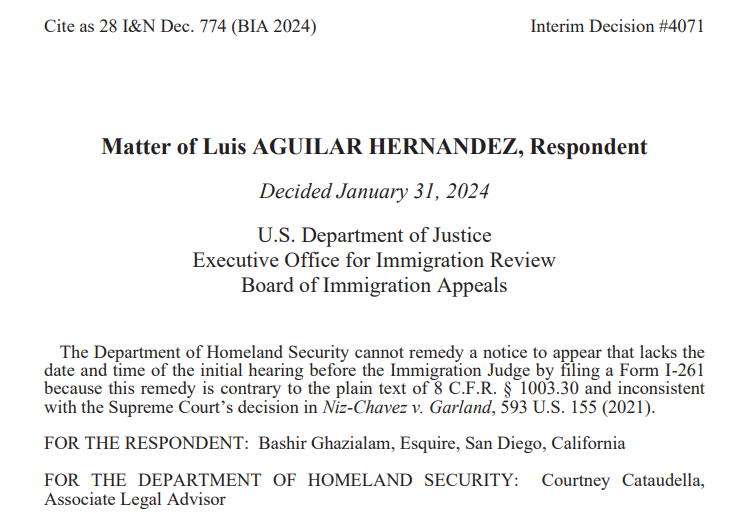

The table below has the Webex link for every Immigration Judge grouped by Court. Updated April 2024 with some additional IJ’s that were not on the prior list. HINT: Use Ctrl+F to search for IJ name. Arizona Eloy Immigration Court Judge Name Internet-Based Hearing Link ACIJ Irene C. Feldman (ICF) https://eoir.webex.com/meet/ACIJ.Feldman Robert Bartlemay Sr. (RCB) https://eoir.webex.com/meet/IJ.Bartlemay … Read more