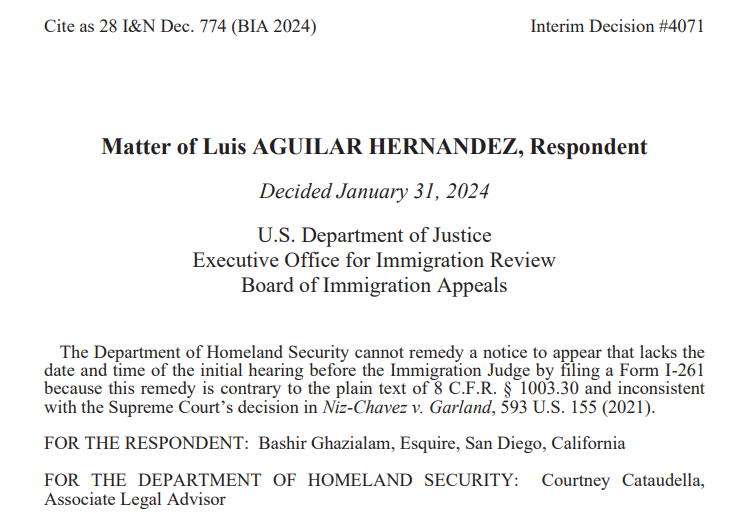

The Sixth Circuit’s Post‑Loper Bright Approach to INA § 1229b(b)(1)(D) in Perez‑Perez v. Bondi

When does a child age-out for purposes of serving as the qualifying relative for 42b Cancellation of Removal? In Roderico Filadelfo Perez‑Perez v. Pamela Bondi, No. 25‑3146 (6th Cir. Nov. 21, 2025), the Sixth Circuit addressed an extremely important question that has caused a divide among the Circuits–At what point in the 42b non-LPR Cancellation of … Read more