2023 US IMMIGRATION DATA

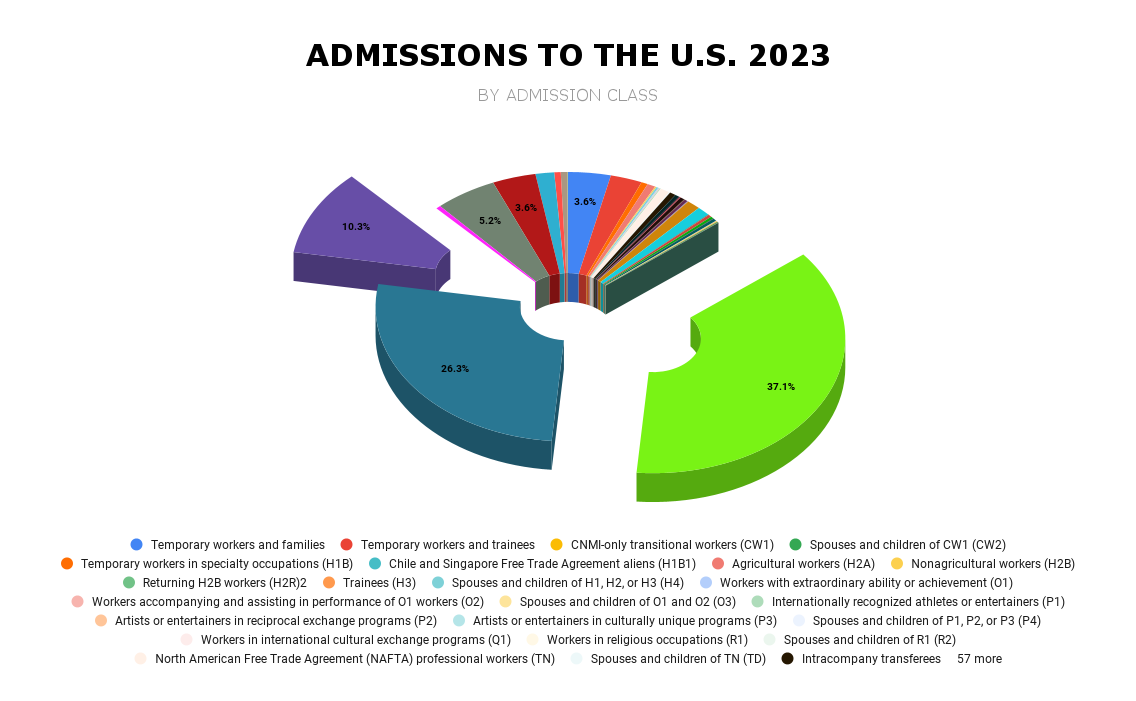

See admissions chart with complete data. NATURALIZATIONS YEAR NUMBER % Change 2023 217,000 -3 % 2022 224,000 Admissions Into The U.S. 2023 Class of admission Total Total all admissions (from PAS)1 60,900,000 Total I-94 admissions 30,750,195 Temporary workers and families 2,284,026 Temporary workers and trainees 1,697,411 CNMI-only transitional workers (CW1) 891 Spouses and children of … Read more